I have four bird feeders in my small urban yard (tube, thistle, platform, hummingbird) but can’t see any of them from my second-story study window, which is veiled by a maple tree far taller than the house. So I fixed a suction-cup window feeder to the upper pane. Earlier in the spring I didn’t get many takers, and those who came grabbed a quick morsel and retreated to the safety of the tree. But the past couple of weeks have seen a constant stream of fledglings: young male cardinals, scruffy and mottled, whom I’ve watched gradually redden and swell; a slender mockingbird who tried out his new repertoire in a nearby branch; a song sparrow who takes his peanut to the stone ledge of the window to peck it to bits; a juvenile house finch who, rather than perching on the feeder’s edge, stands in the pile of seed, hunts for the one he wants, then thoughtfully (as it appears to me) hulls and consumes it while watching me with (what, again, appears to me) casual curiosity three feet away behind glass. The finch is content to occupy the feeder for several minutes at a time while other birds wait in the tree like adolescents in line for the bathroom. Hurry up in there!

Prayer over a dead bird

Photo by Virginia Sanderson.

I’m pretty sure this isn’t theologically correct, but it seemed to help my daughter on our lunchtime walk today, when we found a tiny bird lying on the asphalt, crushed by a car.

Lord, please guide the brave spirit of our brother chickadee to fields that are always green and full of seed, where the insects are plentiful but not too swift, and the skies are ever clear for flying; and make us all more aware of the presence of your beautiful creatures, whatever form they may take. In Jesus name: Amen.

What the snow reveals

Despite preemptive school closings and dire warnings of Black Ice, only a dusting of snow fell here last night — not even enough to cover the ground. A good snow, glistening contentedly in the morning sun, reflecting the clean clear blue sky after the cold front, hides the mess we’ve made of the world and gives the illusion of purity, a new beginning — “a revolution of snow,” as Billy Collins writes:

its white flag waving over everything,

the landscape vanished…

the government buildings smothered,

schools and libraries buried, the post office lost

under the noiseless drift,

the paths of trains softly blocked,

the world fallen under this falling.

But the world was already fallen, and Boris Pasternak thought the snow’s motives less than pure, seeing rather

That snow falls out of reticence,

In order to deceive.

Concealing unrepentantly

And trimming you in white

For Pasternak, indeed, snow may be nothing more than the Altoids on the breath of an alcoholic:

Obsolete constellations

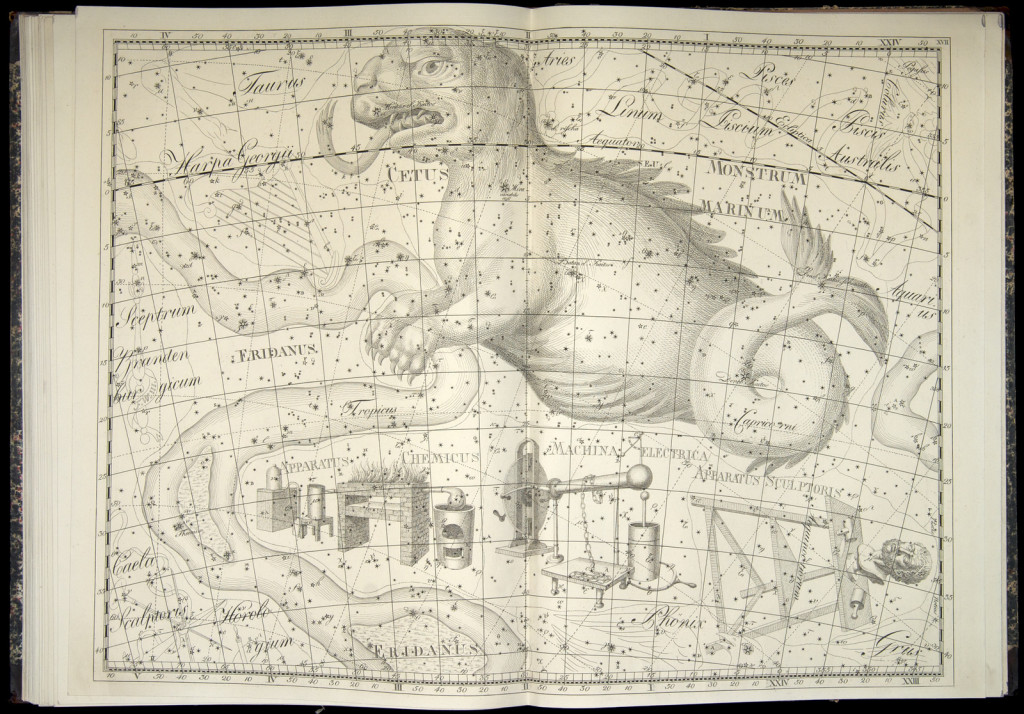

The “Apparatus Sculptoris” constellation in Bode’s Uranographia (via University of Oklahoma History of Science Collections)

Allison Meier shares a look at Johann Elert Bode’s 1801 “Uranographia,” which shows constellations representing, among other things, a printing press and a sculptor’s stand with a partially sculpted head. Until the twentieth century, she notes, “space was a celestial free-for-fall,” with constellations imagined and named and charted willy-nilly. Then the International Astronomical Union, the same body that declared Pluto no longer a planet, designated 88 official constellations, and all the rest are now obsolete.

“It’s fascinating,” Meier concludes, “to gaze back at how our visual culture has long shaped how we perceive those distant luminosities.” Not many of us today, I think, would be likely to see a printing press in the sky, though I’m tempted to look for that sea monster. But the idea that a constellation can be obsolete seems at first blush a bit silly to me; none of them was ever real in the first place, and you either see it or you don’t. But then not many of us in the West see anything in the sky any longer. Now that astrological theories of human health have been thoroughly discredited we have less reason to care. In an era of red shifts and black holes we may lack the imagination. More important, for most of us the sky is too bright. Tonight I should be able to spot Orion, the Pleiades, and… that’s about it. The rest are too dim. Maybe all the constellations are obsolete.

With so few stars to work with, we can’t very easily invent our own constellations any longer, either, even if we were so inclined. I’ve always thought of the constellations as the sum of darkness and idleness. Imagining a bear or a crab, let alone a printing press, in the chaotic infinitude of stars takes time. You have to look at those random points of light, really look, not scanning or searching, without prejudice or purpose, until — delightfully — an image appears. But how many of us are willing to spend an hour or two just looking at anything, let alone a random smattering of light? Or even fifteen minutes? We live too fast, now, to see what isn’t there. That takes time we don’t think we have. Instead we have an international body to tell us what is there, and we Google it and move on. Even the idea of constellations may be obsolete, a relic of a past age — just like that printing press. We have other, faster things now.

In their naked frailty, unable to block the light

In December the sun rises through a copse of trees I can see through my front windows where I sit for morning prayer. Eleven months of the year I see the day dawn only indirectly, as the sun appears nearer due east or northward behind houses or thick pines, or not at all, in the height of summer when the sun is up long before I am. But at the failing of the year the trees stand bare and thin, invisible in the night until the sky lightens behind them, pale at first then golden, the silhouetted branches growing imperceptibly starker until they stretch strong and firm to greet the day. In their naked frailty, unable to block the light, they let it shine through and are strengthened by it. At the failing of the year the dawn is framed for me thus by my window, a promise: The light will ever return, if only we let it.

The river slips softly / into the dusk of the year

Looking eastward down the Eno River, somewhere along Holden Mill Trail, about four-thirty in the afternoon in early November.

On certain autumn afternoons there is a brief passage — if you are lucky you may get ten minutes to appreciate it — when the sun has drifted low and the afternoon breeze has calmed and the light reflects off the surface of the river as from a mirror, doubling the trees and the intensity of their lingering color, and the earth gives the illusion of brightness. The season and the hour have so muted the wood’s palette that the russet of late-hanging leaves calls louder than crimson in June. The sudden splash of gold away downstream beckons like summer’s lost oasis. But the bare arms of sycamore and ironwood make a stark fence against it, and it recedes from my approach — the light, the afternoon, the year. The vestigial warmth of summer dissipates like a mist; winter seeps from the earth and fills its absence.

A crumbling sanctuary of dawn-lit leaves

The east window of my study looks out through a scrim of trees to the neighbor’s golf-green yard and the street and, further on, a young wood of mostly pines. The trees close by appear only as vertical trunks, their leaves cropped out by the window’s frame, but a dogwood leans out low from their shadow and shelters the view with its foliage. For a few short weeks in early fall, when the leaves of the dogwood blushed but still clung to their limbs, the morning light set their edges glowing red-gold, and past their brilliant outlines I could see only the fuzzy blue-green shadow of distant pines. The study became a sanctuary enfolded by copper light, beyond which the world was made misty, unfocused, irrelevant.

That effect lasted only an hour each morning and for two or three weeks. By mid-morning the sun had climbed high enough to light the leaves of the backdrop woods; by the second week of October the dogwood’s leaves had thinned and let the world through in too much clarity. The sanctuary is crumbling now, and what remains is only a relic, like the cracked foundations of an ancient church now open to air and birdflight, in which I sit wondering if God really lived here once.

I got a lot of work done during those weeks.

It is no longer June

By nine the air already sweats.

The sun, wearier today than once

Climbs but slow, as travelers laden

Struggle to heft again damp spirits,

While all around our dizzied ears

This primeval din the wood exudes—

This moldering cacophony

Swells in time with sweltering

And seeps in through our pores like rain.

By nine the air already sweats.

But overhead on fruitless bough

A bird extends his morning song,

Forgetting that it is no longer June.

The turbulence that creates the beauty

From the high ridge the river is placid, dark, smooth, its motion undetectable except by implication of the muddy-pale passage my analytical self knows to be rapids. It winds through the landscape, around unperturbed boulders, past trees positioned as dramatic backdrop by unseen woodsman stagehands. A heron lifts off from some hidden cove and glides easily over the water, ages below me. If the river misses him it keeps its feelings to itself. Occasionally a spot of foam tossed up by turbulence twinkles in the sun, just to keep the viewer interested. Oh, it is beautiful, this placid unmoving scene. It is the beauty of the Grand Canyon, the mountain overlook, the window on the eighty-seventh floor. The beauty of landscape that renders us insignificant before its grandeur and yet also grants us power over it. We comprehend the landscape while seeing nothing of real importance. We look on it with the gaze of science, or of bureaucracy — broad, encompassing, staking authority while proclaiming modesty, underscoring the insignificance of our achievement. From here we are assured that the river runs smoothly on its course, an assurance we have granted ourselves by choosing to remain distant from it. A cold, uneasy beauty.

A cultural sleep

Jessica Gamble describes new techniques and technologies whose inventors would radically reduce or eliminate the human need for sleep:

Transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCS) is a promising technology in the field of sleep efficiency and cognitive enhancement. Alternating current administered to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex through the thinnest part of the skull has beneficial effects almost as mysterious as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), its amnesia-inducing ancestor. Also known as ‘shock therapy’, ECT earned a bad name through overuse, epitomised in Ken Kesey’s novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1962) and its 1975 film adaptation, but it is surprisingly effective in alleviating severe depression. We don’t really understand why this works, and even in today’s milder and more targeted ECT, side effects make it a last resort for cases that don’t respond to drug treatment. In contrast to ECT, tDCS uses a very mild charge, not enough directly to cause neurons to fire, but just enough to slightly change their polarisation, lowering the threshold at which they do so.

Using a slightly different technique — transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), which directly causes neurons to fire — neuroscientists at Duke University have been able to induce slow-wave oscillations, the once-per-second ripples of brain activity that we see in deep sleep. Targeting a central region at the top of the scalp, slow-frequency pulses reach the neural area where slow-wave sleep is generated, after which it propagates to the rest of the brain. Whereas the Somneo mask is designed to send its wearers into a light sleep faster, TMS devices might be able to launch us straight into deep sleep at the flip of a switch. Full control of our sleep cycles could maximise time spent in slow-wave sleep and REM, ensuring full physical and mental benefits while cutting sleep time in half. Your four hours of sleep could feel like someone else’s eight. Imagine being able to read an extra book every week — the time adds up quickly.

The benefits are so obvious that Gamble doesn’t actually argue in favor of all this technological wonder and post-evolutionary glory; instead, she insists that no present-day person can logically argue against it:

The question is whether the strangeness of the idea will keep us from accepting it. If society rejects sleep curtailment, it won’t be a biological issue; rather, the resistance will be cultural…. Such attempts are likely to meet with powerful resistance from a culture that assumes that ‘natural’ is ‘optimal’. Perceptions of what is within normal range dictate what sort of human performance enhancement is medically acceptable, above which ethics review boards get cagey. Never mind that these bell curves have shifted radically throughout history. Never mind that if we are to speak of maintaining natural sleep patterns, that ship sailed as soon as artificial light turned every indoor environment into a perpetual mid-afternoon in May.

Setting aside, for the moment, the matter of sleep, there’s an interesting assumption lurking beneath that paragraph, and I think it’s worth ferreting out, because the opponents Gamble imagines share it.