I’ve long said that any work of art that requires from the outset an accompanying statement to be understood is a poor job of art: if you have a point to make, write an essay. And so I would be content to let the carving above stand on its own. You’ve got music, and flowers, and birds singing—it says love pretty clearly, I hope. (Unless those birds are in fact arguing… it’s hard to tell with birds. Though that might say love just as well. I suppose it depends what they’re arguing about.)

But this carving has roots, and it came about by a fairly complicated process, which may further illuminate it (pun intended).

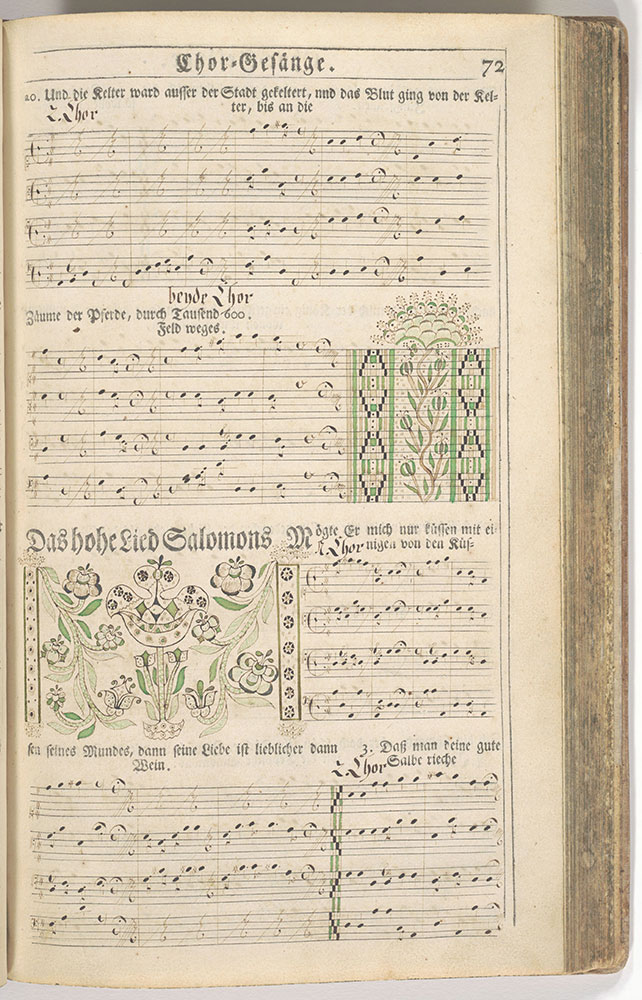

The music is the first bars of “Das Hoheslied Solomons” by Conrad Beissel, founder of the Ephrata Cloister. The hymn appeared in Beissel’s Paradisisches Wunder-Spiel of 1754, accompanied by fancifully hand-painted flowers (shown below). Hoheslied is the German title for the Biblical Song of Songs or Song of Solomon, and the text accompanying the music is a free translation of the opening verse of that book: “Mögte er mich nur küssen mit einigen von den Küssen seines Mundes, dann seine Liebe ist lieblicher dann Wein,” or “O that he would only kiss me with the kisses of his mouth, for his love is dearer than wine.” (The carving shows only the first phrase: “O that he would only kiss me.”)

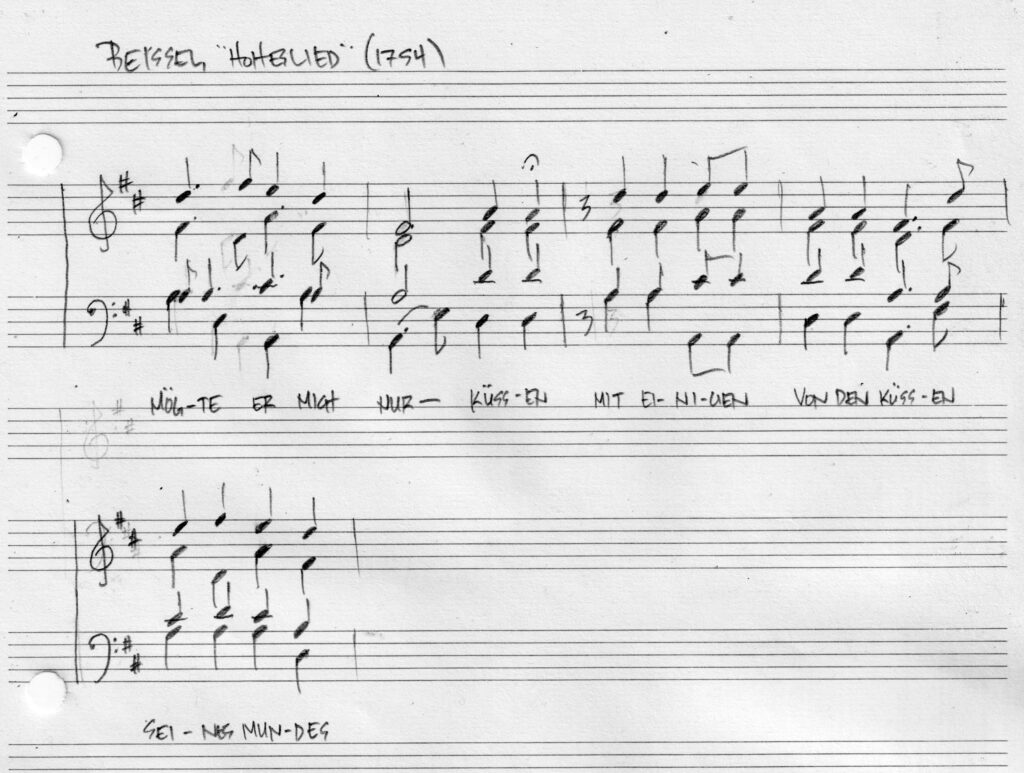

Finding the illuminated page reproduced in the Philadelphia Free Library’s collection I recognized the text but could not at first read the music. There are four separate staves, one for each voice, each with a different clef, and with varying numbers of sharps! Clearly these are It took me longer than it should have to recognize the the letter C indicating that the two accompanying dots mark middle C. The now-standard treble and bass clefs are G and F clefs, marking the indicated note with forms that, as you can maybe see if you squint, derive from those initials—a fact I’d long forgotten, if I ever learned it. Since middle C is above the bass staff, Beissel put a little F clef next to it, so that the C actually marks F, just like a modern bass clef. Then the sharp symbols mark F and C, as they should, and where a staff includes two Fs or two Cs, the sharp is placed on both notes for the singer’s convenience.

Transcribing the lines on G and F clefs, like modern choral music, the shape of the music becomes clearer. The hymn is in D major, as we’d expect from the sharps, and most of the chords are arrangements of the tonic of that key, i.e. D major (D, F#, and A), with some dominant chords (A major, i.e. A, C#, and E). The music works, in other words. But there is one exception: in the second measure, when the bass moves up while the other voices stay constant, for half a beat the resulting chord is a D6, a slight dissonance that immediately resolves into D major.

The text of the hymn is not printed with the notes, and I was unfamiliar with some of Beissel’s notation, so I could not feel sure about the rhythm. I interpreted one of his symbols as shorthand for a dotted-quarter and eighth-note pair, which made the text fit, and it suggests moving chords of the sort one hears in early music. If I’m wrong, I think I’m at least close. Then if you then sing it or recite it in rhythm, you find that the dissonance I mentioned occurs on the word nur—only. If only he would kiss me… Beissel gave that phrase a literal note of longing. Discovering it was like reaching out and touching hands across three centuries.

Now, early Protestants (and some of their descendants) read the Old Testament purely in Christological terms—that is, as pointing to Christ. The Song of Songs, ostensibly a love song between two people rather vividly eager for the marriage bed, thus becomes a hymn about Christ’s love for His church. At the same time, the song’s metaphorical doves and lilies offered Biblically grounded imagery to replace medieval illustrations. All that, certainly, is what Beissel had in mind here, and the painter knew it. The community singing this text in worship was metaphorically longing for the love of Christ.

My own interpretation is that the Song of Songs is exactly what it appears to be: a depiction of a love fully earthly (and earthy) but at the same time holy and blessed. Hence the two birds singing to each other, wreathed by flowers that encircle their own love with a greater love than their own. (And if they are actually arguing, we can hope that greater love helps them resolve their differences.) It is not quite what Beissel had in mind, but he’s dead, so: tough kuche. The seven-point stars of the original, at least, I left alone. And my title acknowledges Beissel’s songcraft, and my debt to him.