As I have spent more time in the workshop the past couple of years I have been thinking more and more about what I do and why I do what I do — that is, work wood with what are commonly called “hand tools.” Certain tasks (like cutting dovetails) take all my concentration, some (ripping 8/4 stock for chair legs) take enough bodily energy that I can’t sustain a complicated conversation with myself, but others (sanding, carving spoons) leave good space for thought, and in that space I find myself asking questions that I am not always able to answer. Questions like: what is a “hand tool,” anyway?

I want to use this blog, in part, to explore those questions, if not necessarily to answer them to anybody’s satisfaction. Rather than starting with what seems like an easy one — what is a hand tool? — I’m going to start in media res, with something I was mulling yesterday: the interconnectedness of tools, materials, methods of work, and the broader economy and culture — what I think of as the “ecosystem” of the workshop. That means starting deep “in the weeds” of the craft and working my way out again. I’ll try to write in a way that gives non-specialists the gist of things without boring woodworkers. That’s a narrow target; forgive me if I don’t quite hit it in a blog post.

So, to begin, a bit of background.

For the past couple of years I have been learning to build chairs. The crest of a chair, the top part you rest your back against, is typically bent — traditionally, by steaming green wood before it has fully dried from the tree, taking wood already fresh and somewhat stretchy and making it more so, then quickly bending it on a form and leaving it to dry and set. If the wood has air-dried, slowly in outdoor racks, it may still be steamed and bent, but with greater difficulty and more risk of breaking. If the wood has been kiln-dried in the modern way, rapidly and with heat, it will have set to the point where steaming likely won’t make it really pliable again. It can be done, but it’s tricky and not really reliable.

The wood I have easy access to is all kiln-dried, and I have not had much success bending it. With more difficulty I can get air-dried oak, with which I’ve had some success if it’s not too dry, but I have to buy a lot of it at a time, and I don’t have much space to store it. I don’t have a good source of fresh-cut, straight-grained logs, and even if I did, again, I’d be at a loss for storage space. So steam bending has been, let’s say, problematic. I basically know what I’m doing — you could say I have proof of concept — but my results are inconsistent.

Steam-bending is a problem I need to solve, but in the short term I’ve taken a recommendation from Christopher Schwarz and turned to “Cold-Bnd Hardwood,” in which by some magical process1in the sense that, as Arthur Clarke observed, all sufficiently advanced science appears as magic to the uninitiated., the wood fibers have been compressed along the grain, so that when the wood is bent, they stretch out again without breaking — meaning that so long as it’s kept relatively moist (about the moisture of fresh-cut wood), it can be bent at room temperature. It’s expensive, but less so in the context of the work I put into a chair; and I can bend it without fuss or haste, even after six months’ storage in the basement wrapped in plastic.

So much for the bending. But the shaping is a mess. The engineered wood fibers tear horribly when planed, no matter the grain orientation. I can use hand planes across the grain to take the wood roughly to my desired thickness, but leveling, let alone smoothing, is nearly impossible. I don’t have big machines; I use hand planes even for the roughest work. But a freshly-sharpened, perfectly tuned handplane makes a mess of this stuff. What to do?

After a couple of really awful experiences I broke down and bought a belt sander, which levels the “dawks” left from cross-grain planing, and use a random-orbit sander to smooth the surface. I wasn’t happy about dropping a hundred bucks on a single-purpose tool, but I’d already spent more than that on the wood itself, and a power tool seemed the most logical solution. And it works!

But there are consequences, and they began to snowball. The new material required a new tool — and a tool that demands a completely different method of use from the hand planes I normally use. It runs on brute force rather than finesse — which necessarily changes the way I relate to the material and to the work, necessarily changes the way I think about the work. It produces dust, a great deal of dust, which has to be managed and collected, and from which I have to protect myself via a respirator and goggles. Rather than working with the material, I’m forced to distance myself from it, both physically and mentally, and force it into shape. The industrial material, in short, requires an industrial tool to be worked, which demand industrial methods of work, which demand industrial thinking. All these things — material, tool, technique, thought — are tangled up together, just as the climate, geology, flora and fauna of a biome are interdependent. Change one element, you may bring the rest crashing down. My hand-tool workshop has a kind of ecosystem — and the cold-bend hardwood was an invasive species.

In fact, the effects ripple beyond my workshop. My hand tools, whether restored antiques or bought new, are with few exceptions made in small shops, or in small factorires in the U.S., Canada, or Western Europe, by workers who understand and use the tools they’re making and are asked to put that knowledge into their work. The belt sander was made in a much larger factory, a necessarily more anonymous setting, in a country where workers have few protections, and its shockingly low sticker price tells me that those workers cannot be treated especially well. My favorite saws are already going on a hundred fifty years old; my hand planes could well outlive me; but that belt sander won’t last 10 years, I’ll wager, and will wind up in a landfill. My one little substitution has impacts that are global and generations long.

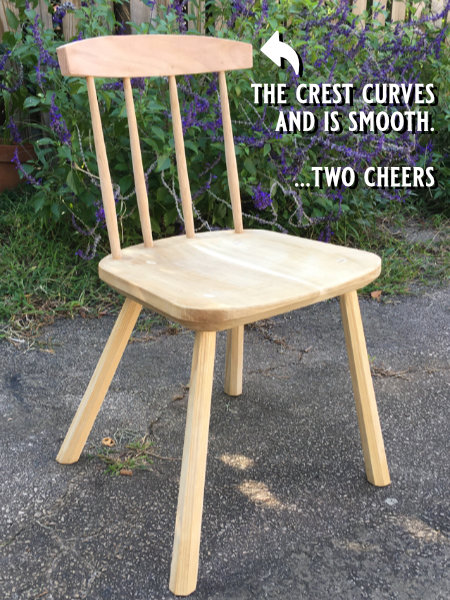

In Where the Wild Things Were: Life, Death, and Ecological Wreckage in a Land of Vanishing Predators, William Stolzenburg explains how the extirpation of wolves and big cats from the forests of eastern North America led to deer overpopulation, which led in turn to the destruction of habitat, the subsequent reduction of insect populations, the loss of songbirds that depend on those habitats and on those insects for food… not to mention deer ticks and Lyme disease. Yesterday, prepping a crest for the bending form, I felt as though I’d shot the last red wolf and the indigo buntings were dropping at my feet. The crest turned out nicely, but it does have me thinking that I need to get back on this problem of steam-bending.

- 1in the sense that, as Arthur Clarke observed, all sufficiently advanced science appears as magic to the uninitiated.