Why do people buy industrial “convenience foods”? Because they’re convenient, of course. We’re busy, and we don’t have time to cook from scratch. Or, rather, we think we’re busy, and we think we don’t have time to cook from scratch. Sometimes that’s the case. More often, the needs we don’t have time to fill by our own labor weren’t really needs in the first place.

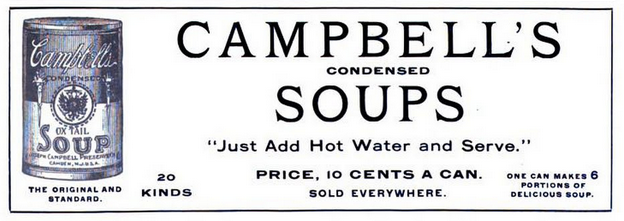

Take, for example, Campbell’s Condensed Soup. When that product was introduced in the 1890s, canned soup had been around for a couple of decades; what was new was the process by which the soup was condensed and the size of the can cut in half, which made the end product cheaper. The earliest ads, placed on streetcars, aimed at the working mothers who rode them, simply showed the can, gave basic instructions (“Just add hot water and serve”), and noted “6 plates for 10¢.” Some of the first magazine ads for condensed soup were placed in the American Federationist, a union magazine. A 1901 ad featured oxtail soup, which, like early soups, was intended as the backbone of a meal.1 For families with little time and little money, then, yes, canned soup seems to have been an obvious convenience.

But that’s only half the story. The other half is that home economists eagerly accepted the new convenience and sold it to middle-class women through the monthly magazines they edited. Not only did general-purpose women’s magazines like Good Housekeeping promote “progressive” cooking, but a few turn-of-the-century magazines devoted themselves entirely to cookery. These magazines offered not only recipes and in-depth discussions of culinary techniques and new products but also gave a month’s worth of daily menus in each issue. By 1904, Table Talk was specifically recommending Campbell’s soups in its menus as replacements for homemade—not every day, but once or twice a week. They didn’t suggest making a meal out of canned soup, even for lunch, but rather serving it as a first course. Here, for example, is Table Talk‘s dinner menu for Tuesday, February 23, 1904: