The angels in Luke’s gospel spend a lot of time telling people not to be afraid. Fear not, Zechariah! Fear not, Mary! Fear not, shepherds!

And over in Matthew, Do not be afraid, Joseph!

They remind me of a guy I used to work for, who often opened his emails with “Now, don’t panic…” When he did that, I knew I was in for it. I knew there was a but coming, and that the but was the point of the message. And that was only my boss. When an angel of the Lord appears unto you, saying fear not, you know that but is going to be a whopper, because angels don’t appear to people to tell them they forgot the milk at the grocery store.

Hey, Joe, now don’t panic, man, keep it chill, but your fiancée’s pregnant by the Holy Spirit. And look, man, we need you to marry her anyway and raise the baby as if it were your own. You’ll face scorn and rejection, but hey, no worries — everything’s going to be all right.

No problem.

Of course when an angel of the Lord tells you that everything will turn out all right, you can safely assume that it will, even if God’s standards for “all right” may not always line up perfectly with our own. And the Christmas story is so thoroughly infused with everything’s gonna be all right that we forget to be afraid when the angel appears. We jump ahead to the scene at the manger, the new baby who never cries, the mother who is not at all tired or sore, the stepfather who does not mind at all having been cuckolded by God or being forced to shelter his pregnant wife and newborn son in a barn, the shepherds slack-jawed in contented wonder, the magi safely arrived with their expensive gifts and nattily dressed entourages. We have viewed that scene so many times that we barely give it a second thought. I see it a half-dozen times just driving into town, spread out in neighbors’ yards.

Not that I object to these displays. The best of them are lovely, the worst are good for a laugh, and nearly all are well meant, if mostly forgettable. A few, though, manage despite their good intentions to undermine any possibility of wonder and awe — like the one in which not only Jesus but Mary and Joseph are depicted as little children, as pudgy, cuddly, roundheaded dollbabies. Even the best creche is safe and unthreatening; dollbaby nativity is merely cute. We have grown so comfortable with the scene at the manger, we have so thoroughly domesticated it and crusted it with sentimentality, that even atheists can gaze contentedly upon it — although when I was one, I managed to be offended that Christians didn’t take their religion more seriously. Babydoll manger scenes seemed like a good reason for me not to take Christianity seriously, either.

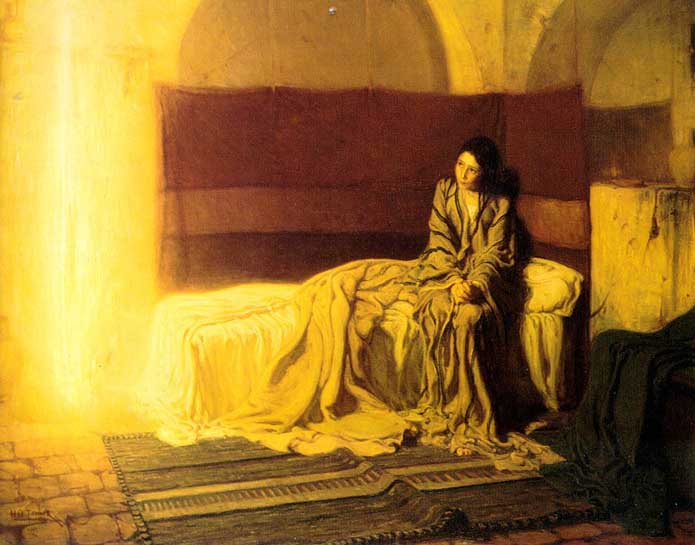

People (and angels) only say fear not when they have the power to frighten you in the first place. The entrance of God into history ought to be a little unnerving. The incarnation of the creator of the universe as a poor and (if only temporarily) homeless kid in a dirty barn ought to be a subject of more than a little concern. The prospect that the entire order of everything is about to be upended ought probably to be cause for nothing short of panic. But that single happy scene at the manger ripped out of context, LED-lit and nestled in the brown grass of the neighbor’s lawn or painted on a Christmas card, prettily smiling girls floating above it, their wings oddly nonfunctional, their halos giving their cheeks a healthy glow? What does that inspire, beyond a vague momentary pleasure?

This domesticated nativity becomes, at best, a somewhat less gritty version of A Christmas Carol. That, too, is a story about spirits and transformation, and we don’t take it very seriously, either. Why would we? It isn’t real. It’s just a story. The ghosts, if not figments of Scrooge’s imagination, are figments of someone’s imagination, and so, therefore, is his fear… and thus also his redemption… and the work he has cut out for him. We, mere readers of a mere fiction, comfortably fear not. Has anyone ever changed their life after reading that story? Why would they? It’s only a story. We feel a little gooey inside, we shed a tear, we close the book, we go to bed.

If, on the other hand, we actually find ourselves believing that the creator of the universe chose to become incarnate as a poor homeless kid in a filthy barn — if, perhaps more to the point, we believe that the creator of the universe is the sort of god who would choose to become incarnate as a poor homeless kid in a filthy barn — then it seems to me we have some real work to do. Everything is going to be all right, yes. In the meantime, God has a few favors to ask of you. Fear not! Rejoice! But.

True joy is always a little unnerving.