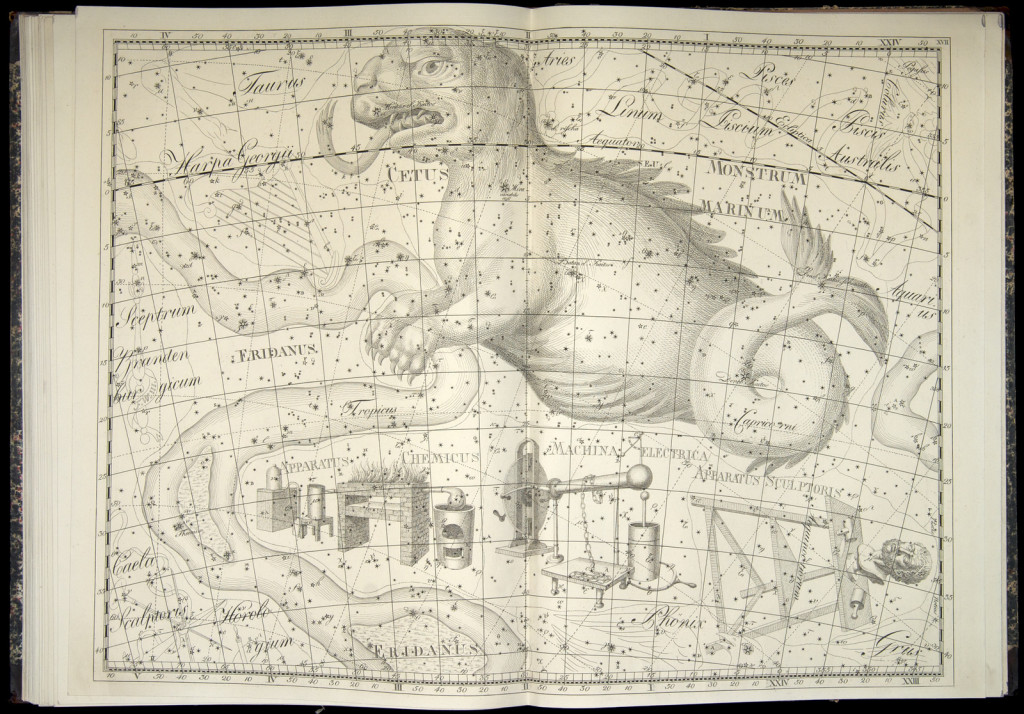

The “Apparatus Sculptoris” constellation in Bode’s Uranographia (via University of Oklahoma History of Science Collections)

Allison Meier shares a look at Johann Elert Bode’s 1801 “Uranographia,” which shows constellations representing, among other things, a printing press and a sculptor’s stand with a partially sculpted head. Until the twentieth century, she notes, “space was a celestial free-for-fall,” with constellations imagined and named and charted willy-nilly. Then the International Astronomical Union, the same body that declared Pluto no longer a planet, designated 88 official constellations, and all the rest are now obsolete.

“It’s fascinating,” Meier concludes, “to gaze back at how our visual culture has long shaped how we perceive those distant luminosities.” Not many of us today, I think, would be likely to see a printing press in the sky, though I’m tempted to look for that sea monster. But the idea that a constellation can be obsolete seems at first blush a bit silly to me; none of them was ever real in the first place, and you either see it or you don’t. But then not many of us in the West see anything in the sky any longer. Now that astrological theories of human health have been thoroughly discredited we have less reason to care. In an era of red shifts and black holes we may lack the imagination. More important, for most of us the sky is too bright. Tonight I should be able to spot Orion, the Pleiades, and… that’s about it. The rest are too dim. Maybe all the constellations are obsolete.

With so few stars to work with, we can’t very easily invent our own constellations any longer, either, even if we were so inclined. I’ve always thought of the constellations as the sum of darkness and idleness. Imagining a bear or a crab, let alone a printing press, in the chaotic infinitude of stars takes time. You have to look at those random points of light, really look, not scanning or searching, without prejudice or purpose, until — delightfully — an image appears. But how many of us are willing to spend an hour or two just looking at anything, let alone a random smattering of light? Or even fifteen minutes? We live too fast, now, to see what isn’t there. That takes time we don’t think we have. Instead we have an international body to tell us what is there, and we Google it and move on. Even the idea of constellations may be obsolete, a relic of a past age — just like that printing press. We have other, faster things now.